The design and implementation of a log-structured file system

‘The design and implementation of a log-structured file system’ by Rosenblum and Ousterhout was published in ACM Transaction on Computer Systems in 1992. The paper introduced the log-based storage which doubles down on the concept of leveraging faster sequential accesses on disks. Even though the log structured file system (LFS) was designed for hard disk drives (HDDs) in the 1990s, its ideas around log-structuring and cleaning have been influential in the design of modern storage systems including file systems, key-value stores, and the flash translation layers (FTLs) of solid state disks (SSDs). We will discuss the motivation and key design aspects of LFS, as described in the paper, while also borrowing from the OSTEP book.

The authors of LFS note that the fast file system (FFS) was not fast enough! Despite its disk-aware layout centered around cylinder groups, FFS tends to spread data around the disk. As a concrete example of this problem, consider the number of accesses required for creating a new small file with FFS. FFS needs to update the file data, the file metadata (file inode), the data for the directory containing the file, this directory’s metadata (directory inode), and the bitmaps that maintain which data and inode blocks are free. All of these structures are stored separately on the disk. To make matters worse, FFS performs these metadata updates synchronously on the disk as opposed to buffering them in main memory and performing them in the background. Because of this, metadata heavy workloads, e.g., workloads that create a lot of small files, become bottlenecked on the disk seeks.

The authors of LFS also observed a technology trend: systems had increasingly large main memory sizes. This trend implied that more and more of the data that applications want to read would be cached in the main memory, leading to reduced read traffic to the disk. Thus the write traffic would dominate disk accesses (writes have to be performed because they cannot be cached in main memory forever). This observation motivated the authors to optimize LFS writes rather than reads.

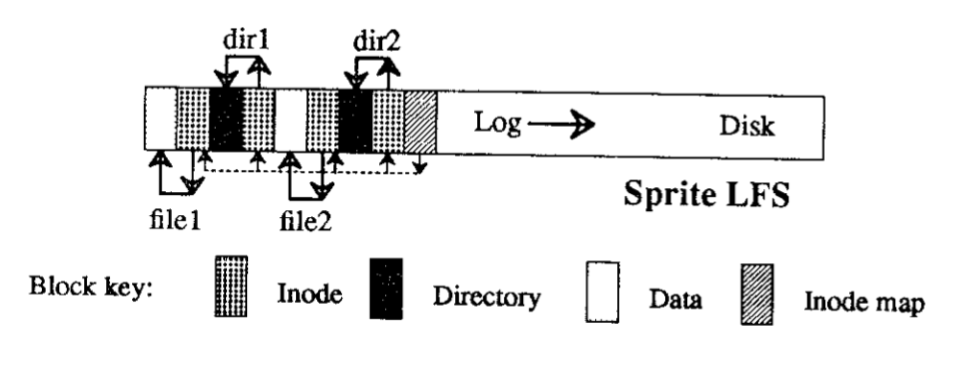

The basic idea of LFS is fairly straightforward: always write to disk in large sequential chunks, termed segments, because sequential writes are faster than random writes on HDDs. In order to do so, LFS buffers blocks in main memory for long-enough to accumulate enough data to fill an entire segment. LFS puts these buffered blocks sequentially in a segment and writes the segment to disk. The log is the one and only source of data in LFS. This design of always writing to the log, and the log being the one and only source of truth also extends to directories, which are just special files whose data consists of a list of files and their inodes.

LFS’s seemingly simple design poses the challenge of finding data in the log. LFS data updates are out-of-place, i.e., when a file’s data is updated, the data is written at a new location (in a block in the new segment) as opposed to the location that held the old data. LFS needs to be able to find the most up-to-date data for any given file block. LFS uses file inodes, similar to FFS, to store the location of data blocks (along with other file metadata like its size and update time). In FFS, file inodes were stored at fixed locations on the disk. LFS could use fixed location inodes, but because each file write requires a write to its inode (recall that a file write changes the location of its data block), LFS would need to update these inode that are not in the log and abandon its always-write-sequentially rule. So LFS stores the inodes in the log as well. This, of course, introduces the problem of how to find the inodes. LFS introduces inode maps to address this problem. Inode maps store the location of an inode indexed by the inode number. This only shifts the problem though - each inode write (triggered by each file write) triggers a inode map write. To ensure that even the inode map writes are sequential, LFS writes the inode map to the log as well (surprise, surprise!) But then, again, how does LFS find the inode map in the log. LFS stores the location of the inode map blocks at a fixed location on the disk (finally!), called the checkpoint region. However, the checkpoint region is written to lazily (e.g., once every 30 seconds) as opposed to for every update to the inode map.

The introduction of inode maps is a classic example of indirection, a common approach for solving problems in computer systems. LFS could have kept the inode maps at fixed location and updated them lazily or even kept the inodes at a fixed location and updated them lazily. However, to be able to update some data lazily, it must be kept buffered in the main memory. By introducing the levels of indirection, LFS reduces the size of data that needs to be cached (one block of checkpoint region can store the location of multiple blocks of the inode map, and each block of the inode map can store the location of multiple inodes)

LFS’s design is clearly optimized for the write-path and has the baked in assumption that frequently read data could be cached in main memory. Indeed, if LFS were to read some data from disk, in the worst case it would require multiple random accesses - first to the checkpoint region, then to the inode map, then to the inode, and then to the (multiple) data blocks, all of which could be spread across the log on the disk. In practice, LFS is able to cache all of the inode map blocks, so it only has to randomly access the inode and data blocks from the disk in a typical scenario.

LFS’s out-of-place updates also necessitate garbage collection of the old data to ensure that the disk does not run out of space. This is reminiscent of the garbage collection problem of SSDs - however, LFS pre-dates SSDs and the garbage collection policies of SSD FTLs are indeed inspired by LFS. LFS garbage collects data by reading the valid data from segments and writing them to new consolidated segments - this process is called segment cleaning. The cost of segment cleaning depends on the utilization of the segments (fraction of live data to total data in the segment) - segments with higher utilization require more cleaning work.

LFS authors first experimented with the seemingly obvious choice of a greedy cleaning policy but found that it is suboptimal for workloads with skewed access patterns that are commonly found in filesystems. File system accesses are often skewed such that a small fraction of files are accessed at a disproportionately higher frequency (e.g., 10% for files are accessed 90% of the time). The files that are updated frequently are said to contain hot data, and files that are updated rarely are said to contain cold data. A greedy cleaning policy, i.e., one which always selects segments with the lowest utilization, keeps selecting the segments with hot data. This has two downsides. First, because the data is hot, their segments require frequent cleaning (the hot data keeps getting outdated soon after cleaning). It would be worthwhile for LFS to wait for longer before cleaning the segments with hot data to amortize the cleaning cost across more updates to the hot data. Second, for segments that contain cold data, it is valuable to clean and consolidate them even if their utilization is low. Because this data is cold, once their segments have been cleaned and consolidated (into, say, a single segment of cold data), the cold segment is unlikely to be updated in near future and require any more cleaning work.

LFS uses a cost-benefit cleaning policy. It balances the cost for cleaning as determined by the utilization with the benefit of the cleaning in terms of the longevity of the cleaned segments. Longevity is the time for which the cleaned data will remain unchanged (and thus, not require cleaning). Of course, longevity is hard to predict because it depends on future accesses. LFS makes the simplifying assumption (a common assumption in computer systems) that history is indicative of the future, substituting longevity (how long will a data block live) with age (how long has a data block lived). Segments with cold data are considered to have higher longevity and can thus be cleaned at a relatively higher utilization. LFS tracks the utilization of a segment and its age (in terms of the time of the most recent modification to any block in the segment) in a segment usage table.

The LFS paper describes many other nitty-gritty details that go towards making the seemingly simple design choice of LFS work. The paper also discusses crash recovery, an important aspect of file systems, in detail. We will discuss crash recovery in a future post wherein we will compare and contrast some of the classical crash recovery mechanisms including that of LFS. So long, and thanks for reading!